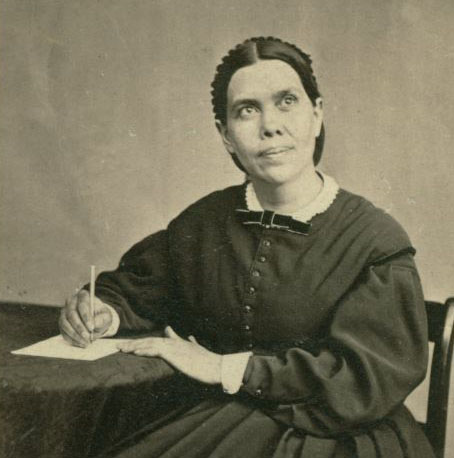

In 1891, Ellen Gould White - the beloved prophetess of the Seventh-day Adventist denomination - delivered a historic speech titled: “Our Duty to the Colored People.”

“This watershed message to the General Conference session in Battle Creek (Michigan) was the first major appeal to the SDA church on behalf of developing a systematic work for Black people in the South,” wrote Delbert Baker, an Adventist historian and church leader, in an online series titled “In Search of Roots: Adventist African-Americans.”

Now, 128 years later, black Adventists account for about 32 percent of Seventh-day Adventists in the United States, just five percentage points less than white members, who now make up 37 percent, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center Religious Landscape Study.

Those percentages differ from a 2018 demographic study conducted by Adventist researcher Monte Sahlin on behalf of the North America Division. According to that study, which researched a larger SDA sample, the denomination’s NAD ethnic make-up is 51 percent white, 15. 7 African American, 9.5 percent Caribbean, 11 percent Hispanic percent, 7.6 percent Asian and 11.8 percent of mixed race. The NAD study includes results from Canada.

Adjusting the numbers for the 3 percent sampling error, Sahlin said the numbers would be closer to about 51 percent white, 16 percent African American, 9.5 percent Caribbean, 11 percent Hispanic and 11 percent multiethnic or other.

In both cases, the percentages are a stark contrast to the general U.S. population, where whites account for about 77 percent of the population, Hispanics for about 17 percent and blacks for approximately 12 percent. Much of the recent growth has occurred among black Adventist immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa and Latin America.

Yet, like other American institutions, the SDA denomination has struggled with race relations. One practice that remains a thorne in the flesh of the organization is the existence of conferences designated by race in the United States. Since the 1940s, the NAD has had black and white conferences, a tradition that dates back to the establishment of black “regional conferences” when America was very much a segregated society. Today, the church still has nine predominantly black regional conference in the United States.

The denomination's first debates over the issue coincided with its early expansion. In 1891, Ellen White faced a daunting challenge as she advocated on behalf of former black slaves in the wake of the Civil War. For many years, church pioneers had focused on expanding the Adventist faith westward from the shores of New England, where the denomination first originated. Following emancipation, some denominational workers attempted to uplift the newly freed slaves, but their efforts were hindered by violent opposition from Southern segregationists.

“During the General Conferences of 1877 and 1885, the question of bowing to prejudices by establishing segregated work and churches was debated,” wrote Richard Schwarz and Floyd Greenleaf in their book, Light Bearers: a History of the Adventist Church. “Most speakers believed that to do so would be a denial of true Christianity since God was no respecter of persons.

“In 1890, however. R.M. Kilgore, the Adventist leader with the most experience in the South, argued for separate churches,” the authors continued. “D.M. Canright had urged this policy as early as 1876 while working briefly in Texas. Eventually, their recommendations prevailed, but the policy was never defined on grounds other than those of expediency.”

By 1891, White felt compelled to address the issue, stating that God had no preference of skin color and pitied “those who are called to bear a greater burden than others.” In her writings, she penned these words:

“I am burdened, heavily burdened, for the work among the colored people…For many years I have borne a heavy burden in behalf of the Negro race. My heart has ached as I have seen the feeling against this race growing stronger and still stronger, and as I have seen that many Seventh-day Adventists are apparently unable to understand the necessity for an earnest work being done quickly. Years are passing into eternity with apparently little done to help those who were recently a race of slaves.”

At the same time, her son, James Edson, was just returning to denominational ministry. After reading his mother’s writings, he was impressed to evangelize blacks in the South. He commissioned the building of a steamboat, “The Morning Star,” which became a “floating headquarters (complete with chapel and print shop) for publishing, evangelistic, educational, and agricultural work among Mississippi black people,” according to an article by Roy Branson.

“This Mississippi River steamboat steamed up and down the Mississippi waterways for close to a decade,” Baker wrote in his historical piece. “... The Morning Star represents the first serious organized effort by Adventists for Black people.”

In 1896, the church continued with its work among black Southerners, establishing Oakwood Industrial School in response to White’s insistence that leaders launch a training school for former slaves. Located in Huntsville, Ala, the college, now Oakwood University, began on a 360-acre farm, which later expanded to 1,000 acres.

Yet, despite such acts of benevolence toward African-Americans, the Seventh-day Adventist Church has grappled with the integration of ethnicity and culture throughout its history.

“One of the knotty social issues that haunted the church from its early days was the question of ethnic diversity,” wrote Schwarz and Greenleaf. “Its most virulent manifestation erupted in relations between Black and White Adventists. It was in the United States itself that the church first faced the problem when workers ventured from the northern to the southern part of the country following the American Civil War.”

Dana Edmond serves as director for the Office of Regional Conference Ministries based in Huntsville, Ala. While speaking with students in the Interactive Journalism class at Southern Adventist University, he reflected on the church’s racial divide, historically. He said regional conferences started 75 years ago when the church faced a racial crisis, not in the Deep South but the northeastern United States.

A light-skinned church member, Lucy Byard, had become ill while attending a General Conference Session in Washington, D.C. She was admitted to an Adventist hospital. When hospital workers discovered Byard was mulatto, they un-admitted her and sent her across town to a black hospital. She died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

“That caused quite a bit of ruckus,” Edmond said. “And so, the Adventist church was faced with one of two choices: They could fully integrate or they could give black people what's called regional conferences. The church chose instead of integration to give black people their own conferences."

Regional conferences were authorized by this action of the General Conference Spring Council in 1944:

“WHEREAS, The present development of the work among the colored people in North America has resulted, under the signal blessing of God, in the establishment of some 233 churches with some 17,000 members and

“WHEREAS, It appears that a different plan of organization for our colored membership would bring further great advance on soul-winning endeavors, therefore

“WE RECOMMEND, That in the unions where the colored constituency is considered by the union conference committee to be sufficiently large, and where the financial income and leniency warrant, colored conferences be organized.”

Today, the nine black conferences consist of over 300,000 members of various ethnics backgrounds, including many Caribbean, Latin American and African immgrants. “Regional conferences endorse the General Conference imperative of an open fellowship and are racially and nationally diverse,” according to the Office of Regional Conference Ministries website. “Although originally planned for Black people alone, many congregations within the regional conferences are predominantly Hispanic, Korean, Haitian, African and White. Lovingly, they all remain open and embracing to anyone the Lord sends to join them in their daily walk to the kingdom. Regional conferences consistently baptize 8,000 to 10,000 new members per year.”

Despite the racial separation, "the Lord has actually blessed,” Edmond said. “… At the time that regional conferences were started 75 years ago, there were only about 18,000, black Seventh-day Adventists in North America. Today, just counting the ones in regional conferences, there are about 320,000 people, … which means the work among African Americans and regional conferences has increased 16 times, whereas the work in the rest of North America has grown at a respectable four times. So, the rate of growth in regional conferences is four times the rate of the rest of the work in North America.”

The Office of Regional Conference Ministries recently broke ground on a 30,000-square-foot office complex in Huntsville, Ala. The building will house an office for regional conference retirement benefits, the organization's newspaper the Regional Voice, and Breath of Life Television Ministries.

Edmond described himself as a third-generation Seventh-day Adventist and a product of the church's educational system. He is in his 41st year as an Adventist minister and loves the church dearly, he said.

“... But the harsh truth of the matter is, though the Seventh-day Adventist church is God's remnant church, it has a very ugly history as it relates to racism,” he told the students at Southern. “There was a time that the very fine school that you young people attend -- a school for which I was a member of the Board of Trustees for seven years – there was a time when African Americans couldn't get into Southern.

“... There was a time when if you went to the General Conference to eat and you were African-American, you couldn't eat at the cafeteria. … If you could get into this school, you couldn't just sit down anywhere you wanted. We had segregated tables.

“So, for the Adventist church to be graded as the most diverse church means that we've come a long way,” he said. “But we have what I call ‘one-way diversity.’ That is, we have integration and diversity primarily because people of color leave institutions of color and join the majority culture institutions. That’s why Southern is integrated and Oakwood (a historically black university) isn’t.

“So, the challenge that we have now is to move from one-way integration, which is what we have now, to full integration.”

Some leaders and constituents have called for black and white conferences to merge, but Edmond said he diagrees with that option.

“Anytime we talk about diversity, we only talk about people of color closing down their institutions and joining the majority culture,” he said. “And that is actually an insult.”

Alexander Bryant, executive secretary of the North American Division, said some people ask whether the denomination has outgrown its segregated history.

“And that question everybody has to answer in their own minds,” said Bryant, who is also African-American. “The question I would ask is: Are we still mirroring what's happening in society today? And are we doing it the same way? I think until we can get away from that, and act like and be like the people of God, we will always have this issue.”