When I was 11 years old, my world was turned upside down. Up until that time, I had spent most of my life in Chile – a place where my family and I were foreigners, but we still called home. I embraced the environment that surrounded me and celebrated the same traditions as my friends.

Everything changed in 2009 when my family decided to move to the Philippines.

I felt completely lost. Everything, from the language to the food, was different. It was an immense cultural shock that left me crying for some normality.

What made things even more difficult, however, was that the shock came from various cultures, not just the Filipino one.

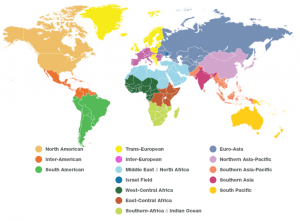

My father was a professor at an international institution, where than 50 countries were represented. Many families – – just like mine — had been living in their home countries, emerged in their cultures. They had just moved to a new environment, which became a melting pot.

For a long time, it was a struggle. Yet, as time progressed, I actually learned to appreciate the various cultures around me as much as my own.

Here are five steps that helped me do so. And I hope they help you, too.

I knew my own culture

This may sound silly, or even counterproductive (why am I looking at my culture when I am trying to learn about a different one?). But getting to know one’s own culture is the first crucial step to take when learning to appreciate others. We may not always realize it, but the culture in which we are raised has helped shape the way we view the world. Our opinions, assumptions and even the way we think is somehow shaped by the customs we follow.

There are certain things we may scorn because our own culture has taught us to do so. For example, why was I disgusted when someone would slurp on their soup? Because in my culture that is impolite to do. But just because it is rude in my culture does it actually make it wrong? If we understand from where that judgment originates, then we open ourselves to see things from a different perspective.

Ask yourself:

How has my worldview been affected by my culture?

What part of my culture is holding me back from understanding someone else’s?

Quote:

“Your culture is your limit; if you can’t go beyond it you will remain as a frog of your little lake.” – Mehmet Murat Ildan

I was open to other cultures

One of the things that bothered me in the Philippines was having to take off my shoes whenever I went to a friend’s house. What if their floor was dirty? What if my feet got cold? What was the point of all this fuss?

To me it was ridiculous. Then I learned that in many Asian cultures home is viewed as one’s private space and traditionally history most things were done on the floor (Yes, even eating and sleeping). So, the fact that someone is inviting you to their personal space, means they are opening themselves to you. Taking off your shoes means that you appreciate and respect that act of kindness.

If we do not try to learn about someone’s culture, then we will miss the chance of seeing the beauty behind each tradition.

Ask yourself: What can someone’s culture teach me about the person?

How will understanding their culture help me see the beauty in their traditions?

Quote:

“When you learn something from people, or from a culture, you accept it as a gift and it is your lifelong commitment to preserve it and build on it” – Yoyo Ma

I tried new things

Growing up, I was a picky eater. That is why my first potluck in the Philippines consisted of me wrinkling my nose as I scanned all the dishes I knew I was not going to eat. This was the first time I had seen food from places such Thailand, Kenya or China. The food looked weird; it looked different. Even with the variety of choices, I ended up having what my mom had brought.

Now, imagine my surprise when I tried all those different foods and found out how delicious they actually were. Soon enough, dumplings, pancit, tkeok-bokki, curry and chapatti became my favorite meals. But even more importantly, I became a fan of trying new cuisine.

One of my personal and favorite theories is that to truly know a country’s culture you have to try their street food. Yet, this was something I would have never discovered if I had not allowed myself to try.

Ask yourself: What could I be missing because I am not trying? What choices could I make to change that?

Quote:

“Never be afraid of trying something new, because life gets boring when you stay within the limits of what you already know” – Unknown

I respected other traditions

While I tried to learn and appreciate other cultures, there were certain things that I could not fully comprehend. I learned that we are all unique and hold various viewpoints.

Disagreements are bound to occur. However, it is important to realize that though we may different times, it does not give us the right to disrespect other people or their cultures.

No culture is superior to another. Despite what ethnocentrism tries to teach, all cultures hold the same value and are special in their own ways.

Ask yourself: Do I want others to respect me and my culture? Am I showing that kind of respect to those who are different from me?

Quote:

“It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.” – Audre Lorde

I built relationships

One of the cultures I had the hardest time relating to was the Korean culture. Though I had tried my best to enjoy the traditions, it just seemed like I could never quite get there.

A majority of my classmates were Koreans, and whenever I was around them I felt lost and out of place. I respected them, but I still was unable to appreciate their traditions like I appreciated others.

Then during my freshman year of high school, I became friends with a girl named Deborah. I did not know it then, but she would become one of my dearest friends. Talking to her did not only give me the chance to get to know her as a person but also a chance to see the Korean culture in a new light.

Ask yourself: What have I learned from the friends I already have? How can I expand my circle of friends?

Quote:

“Every person is a new door to a different world.” – Unknown

When I was 16, I got my first job at McDonald’s. I was determined to start my own savings and be able to purchase most of my own things.

When I was 16, I got my first job at McDonald’s. I was determined to start my own savings and be able to purchase most of my own things.