In the video above, Madeline Mace, junior fine arts major, describes her journey with art and shares insight into the inspiration behind her pieces.

By Natalia Perez

This week, I interviewed four Southern students on their backstories as creators, and how their religious affiliation or cultural/societal gender roles have affected — or not affected — their creative process and expression.

Barry Daly, senior religious studies major, is an imaginative and detailed artist. He has been creating as a photographer for seven years.

Barry Daly, senior religious studies major, is an imaginative and detailed artist. He has been creating as a photographer for seven years.

Tell me a bit about you as an artist.

B: “For the majority of my life, I’ve tried my best to create from my imagination through writing, storytelling, and filmmaking. When I was starting out I would draw [inspiration] from everywhere, and as a result, I was able to draw emotion from my subjects that many other photographers could not. At this point in my creative journey, I draw from minor details in conversations, certain body language, details in movies, music, or other forms of entertainment.”

For more on Barry’s work, visit https://www.procltv.com/

Audrey Fankhanel, junior international studies major, has been especially flourishing as an artist during her year abroad in Italy. She creates through writing, photography, painting, and designing.

Audrey Fankhanel, junior international studies major, has been especially flourishing as an artist during her year abroad in Italy. She creates through writing, photography, painting, and designing.

A: “It is hard to become an artist. It’s something that is innately within you. I have been creating since before I can remember. I have a portfolio for every year of my life, each filled with short stories and paintings. However, I still struggle with calling myself an artist because by claiming the title I feel a huge responsibility and pressure to create.

I am most inspired by nature, but my works are not directly about nature. I’m fascinated by the rhythms and patterns found in every aspect of the natural world, from the orbit of an electron to the ever-expanding universe. This life is so unpredictable, but these natural laws are perfect and never changing, and if that isn’t evidence of a God then I don’t know what is.”

For more of Audrey’s work, visit https://www.auddities.co/

Kristen Vonnoh, senior journalism-publishing major, has a special flair in her writing that matches her personality. Her writing interests include faith, fashion, and music among other things.

Kristen Vonnoh, senior journalism-publishing major, has a special flair in her writing that matches her personality. Her writing interests include faith, fashion, and music among other things.

K: “I guess my writer’s journey began when I made a blog in fifth grade documenting horribly written short stories. I never really considered calling myself a writer until college, and even now I typically call myself a journalist. But I suppose “writer” is all-encompassing, which I like.

I definitely tend to be the overly dramatic, overly romantic type, so I draw creativity from pretty much everything honestly. Whether it’s a super mediocre cup of coffee or a TED talk I just heard, my mind is constantly absorbing ideas for my writing. That and my journalism professors have given me the wonderful advice to always, always, always be looking out for interesting stories.”

To read Kristen’s work, visit https://www.kristenvonnoh.com/

To read her blog, visit https://kristenstagram.com/

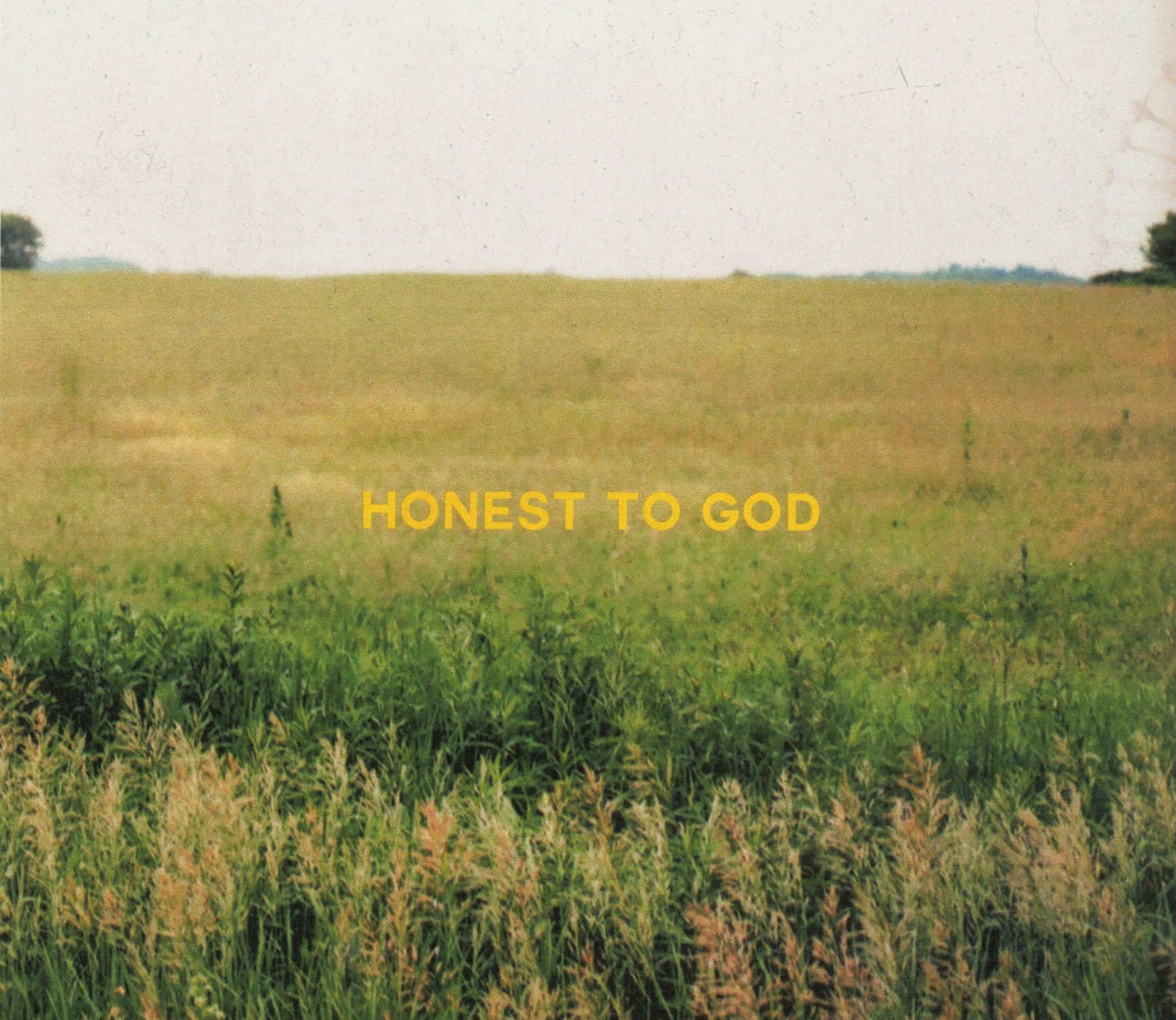

Jordan Putt, Southern alum, is a soulful and heartfelt creative. On April 21, 2018, he released an EP called “Honest to God,” available on Spotify, Apple Music, Bandcamp, and all music online-streaming sites. His album is a meditation of God, humanity, imperfection, and faith; and it’s the culmination of almost four years of sporadic writing. His music reads like a love letter to a best friend.

J: “I’ve been interested in music for as long as I can remember. Since I was old enough to pull myself up onto the piano bench, I would pretend to play music on it. I got my first guitar when I was 10, and it’s been a love affair ever since. I draw inspiration from my own experiences and feelings, as well as whatever I happen to be listening to at the moment. I think one of the things that has helped me become a better musician is listening to music from as wide a variety of musical genres and eras as I possibly can. I get a lot of inspiration from hearing what other people have done and trying to assimilate that into my own playing and writing.”

To listen to Jordan’s EP, visit http://distrokid.com/hyperfollow/jordanputt/dciF

Here’s more of what the four artists had to say on this topic:

Do you feel limited by our religion or do you feel it enhances your creativity?

B: “When I was younger, I really believed that anything was possible within the confines of the church. As I have gotten older, I’ve consistently encountered judgment and opportunism. For the longest time, I had no idea why so many made the decision to leave the church. Often times, church-goers don’t take the time to really show love and support artists. Ultimately, I don’t believe that religion and belief limit me, but the people who “control” them do their best to shame creatives into fitting in the box they’ve built.”

A: “Growing up surrounded by the Adventist culture in Loma Linda, California, I absolutely have felt limited creatively. My spiritual beliefs enhance my art more than anything else, but the religious culture in which my beliefs reside creates a bubble of “appropriateness” that SDA’s are expected to operate within.”

K: “I 100% believe my relationship with God fuels my creativity. Understanding the gospel and my freedom in Christ has only allowed my creativity to flourish. And I think the key in all of that is a relationship with God—the ultimate Creator.”

J: “I feel less limited by my beliefs than by what I think my audience will tolerate. My beliefs go hand in hand with my experiences and who I am as a person, so as long as I stay true to myself in my art (which has always been my goal), I won’t even think about creating something that goes against my beliefs. However, I do think that there are a lot of taboos in Adventist culture as it relates to doubts, struggles, and questioning. I have felt like there’s a lot of pressure to put on a good face and appear secure and content all the time, even when that may not be the case. This can be especially true for people who have been raised in the church.

For me, the anxiety that comes from being vulnerable and open about those questions or struggles can sometimes cause me to feel limited in what I feel comfortable talking about because of how I think it may cause my audience, especially the more conservative segment, to perceive me as a person.”

What do you think differentiates traditional feminine art from masculine art?

B: “I believe that the biggest difference is that most often it’s much easier for women to show emotion, and they are most often more willing to be vulnerable because for them art is healing.”

A: “Traditionally, masculine art has dominated feminine art, and this is mainly at the fault of the consumer. Male artists are given unwritten permission to be provocative and enticing. Their works tackle big ideas and complex emotions. Meanwhile, females are associated with creating “pretty” paintings or fun business logos. There are many female artists creating just as great works as males, but you will never hear about them. This goes for the Christian church as well, especially if you look at preaching as an art form. How many mega churches do you see being spearheaded by women? How often do you hear of a great female theologian outside of the context of an “inclusion” seminar?”

K: “I’ve always found this idea interesting because while there are universal feminine and masculine characteristics, much of it is also determined by culture. As a woman going into the field of journalism, I definitely recognize the “masculine” aspects of the craft (i.e. analyzing, collecting data and documents, etc.) and honestly I love it because it pushes me out of my comfort zone and forces me to engage with a different aspect of my mind.”

J: “I think art that we perceive as feminine usually tends to deal with softer, more traditionally feminine themes — love, family, etc. What is generally perceived to be masculine art usually deals with things that are traditionally male themes or traits, such as aggression, strength, security, etc.”

When I was 16, I got my first job at McDonald’s. I was determined to start my own savings and be able to purchase most of my own things.

When I was 16, I got my first job at McDonald’s. I was determined to start my own savings and be able to purchase most of my own things.